Flare-On 2017 writeups

byOctober 14, 2017

Flare what?

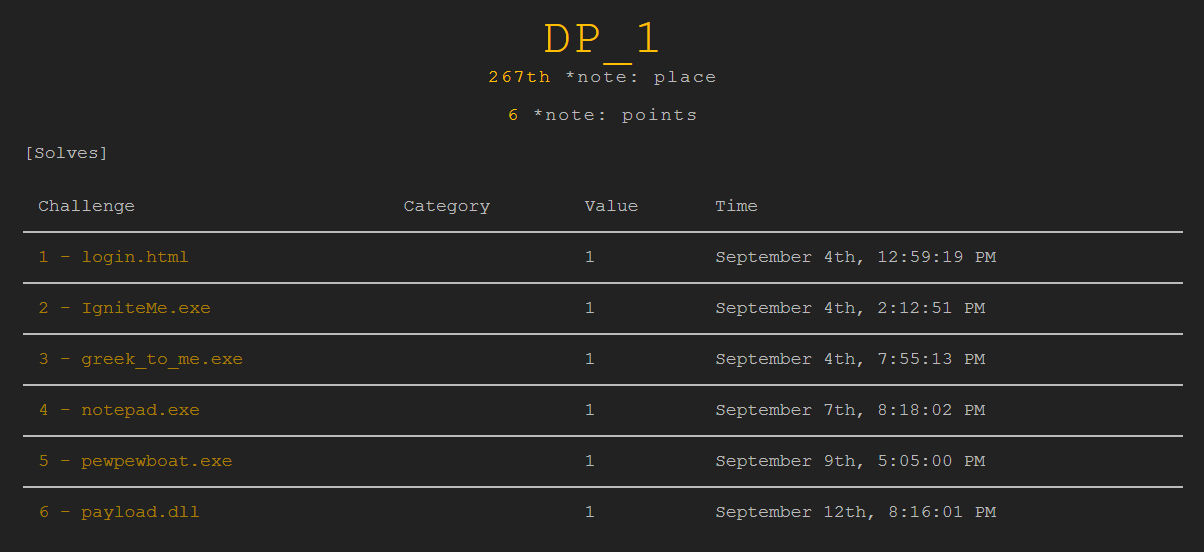

The Flare-On competition is an annual reverse engineering competition run by FireEye and mostly Windows-based. This was the first time I took part in it, and I have to admit some of the challenges were, uhm, challenging. In the end I managed to solve the first six problems out of 12.

Challenge 1: login.html

“Welcome to the Fourth Flare-On Challenge! The key format, as always, will be a valid email address in the @flare-on.com domain.”

For the first challenge we get an HTML document. Opening it in a browser reveals a form for checking the flag. Once we view the script contained in the source code we basically have the flag in plain sight:

<script type="text/javascript">

document.getElementById("prompt").onclick = function () {

var flag = document.getElementById("flag").value;

var rotFlag = flag.replace(/[a-zA-Z]/g, function(c){return String.fromCharCode((c <= "Z" ? 90 : 122) >= (c = c.charCodeAt(0) + 13) ? c : c - 26);});

if ("PyvragFvqrYbtvafNerRnfl@syner-ba.pbz" == rotFlag) {

alert("Correct flag!");

} else {

alert("Incorrect flag, rot again");

}

}

</script>

All that’s left to do is to apply the ROT13 algorithm to “PyvragFvqrYbtvafNerRnfl@syner-ba.pbz”

in order to get the flag:

ClientSideLoginsAreEasy@flare-on.com

Challenge 2: IgniteMe.exe

“You solved that last one really quickly! Have you ever tried to reverse engineer a compiled x86 binary? Let’s see if you are still as quick.”

This time we get a windows executable to work with, IgniteMe.exe. When we run it, we’re prompted with the uber-l33t statement "G1v3 m3 t3h fl4g:". Putting in a random string only gets us to the even l33t3r "N0t t00 h0t R we? 7ry 4ga1nz plzzz!" After opening the file in IDA we can see that it xor encrypts the input and checks it against some data. sub_401000 is used to get an initial seed, which I found out to be the number 4 using the debugger. Then the rest easily followed, I wrote the inverse algorithm into the following program and run it to get the flag:

#include <cstdio>

char data[39] = {0x0D, 0x26, 0x49, 0x45, 0x2A, 0x17, 0x78, 0x44, 0x2B, 0x6C, 0x5D, 0x5E, 0x45, 0x12,

0x2F, 0x17, 0x2B, 0x44, 0x6F, 0x6E, 0x56, 0x09, 0x5F, 0x45, 0x47, 0x73, 0x26, 0x0A,

0x0D, 0x13, 0x17, 0x48, 0x42, 0x01, 0x40, 0x4D, 0x0C, 0x02, 0x69};

char result[40];

int main()

{

int key = 4;

for(int i = 38; i >= 0; i--)

{

result[i] = data[i] ^ key;

key = result[i];

}

result[39] = '\0';

printf("%s\n", result);

}

It quickly gave me R_y0u_H0t_3n0ugH_t0_1gn1t3@flare-on.com as the answer.

Challenge 3: greek_to_me.exe

“Now that we see you have some skill in reverse engineering computer software, the FLARE team has decided that you should be tested to determine the extent of your abilities. You will most likely not finish, but take pride in the few points you may manage to earn yourself along the way.”

Initially when we run the program nothing seems to happen, but by opening it in IDA it is easy to see that it is listening for a TCP connection from localhost on port 2222. It then proceeds to read up to four bytes in sub_401121, of which only the first one will ever be used. At first the disassembly of main looks weird, including undocumented opcodes and kernel mode instructions, alongside with accesses to invalid memory locations. Have a look:

loc_4010A0:

icebp

push es

sbb dword ptr [esi], 1F99C4F0h

les edx, [ecx+1D81061Ch]

out 6, al

and dword ptr [edx-11h], 0F2638106h

push es

[...many similar instructions...]

push es

sub dword ptr [ebx+6], 6EF6D81h

xor dword ptr [edx-17h], 7C738106h

If we try to send something via netcat we always seem to get “Nope, that’s not it”. What’s happening behind the scenes is that the first byte received is used as a key in a simple xoradd decryption scheme, where each of the 121 bytes of the weird looking code is first xored with the key and then incremented by 34. Afterwards a 16 bit hash of the decrypted data is calculated and checked against 0xFB5E for equality. If the hash matches, the code is executed, otherwise we get to the same error message as before. We could either run through all 256 possible input bytes by hand, or copy the algorithm and brute force the solution programmatically. I, for obvious time reasons, chose the latter and wrote the following C++ code that quickly gave me 0xA2 as the key:

#include <cstdio>

#include <cstdint>

uint8_t data[121] = {0x33, 0xE1, 0xC4, 0x99, 0x11, 0x06, 0x81, 0x16, 0xF0, 0x32, 0x9F,

0xC4, 0x91, 0x17, 0x06, 0x81, 0x14, 0xF0, 0x06, 0x81, 0x15, 0xF1,

0xC4, 0x91, 0x1A, 0x06, 0x81, 0x1B, 0xE2, 0x06, 0x81, 0x18, 0xF2,

0x06, 0x81, 0x19, 0xF1, 0x06, 0x81, 0x1E, 0xF0, 0xC4, 0x99, 0x1F,

0xC4, 0x91, 0x1C, 0x06, 0x81, 0x1D, 0xE6, 0x06, 0x81, 0x62, 0xEF,

0x06, 0x81, 0x63, 0xF2, 0x06, 0x81, 0x60, 0xE3, 0xC4, 0x99, 0x61,

0x06, 0x81, 0x66, 0xBC, 0x06, 0x81, 0x67, 0xE6, 0x06, 0x81, 0x64,

0xE8, 0x06, 0x81, 0x65, 0x9D, 0x06, 0x81, 0x6A, 0xF2, 0xC4, 0x99,

0x6B, 0x06, 0x81, 0x68, 0xA9, 0x06, 0x81, 0x69, 0xEF, 0x06, 0x81,

0x6E, 0xEE, 0x06, 0x81, 0x6F, 0xAE, 0x06, 0x81, 0x6C, 0xE3, 0x06,

0x81, 0x6D, 0xEF, 0x06, 0x81, 0x72, 0xE9, 0x06, 0x81, 0x73, 0x7C};

uint8_t buf[121];

uint16_t hash()

{

uint32_t len = 121;

uint8_t *input = buf;

uint16_t i = 0;

uint16_t v3 = 255;

for(i = 255; len; v3 = (v3 >> 8) + (uint8_t) v3)

{

int v6 = len;

if(len > 20)

v6 = 20;

len -= v6;

do

{

i += *input;

v3 += i;

++input;

--v6;

}

while(v6);

i = (i >> 8) + (uint8_t) i;

}

return ((i >> 8) + (uint8_t) i) | ((v3 << 8) + (v3 & 0xFF00));

}

int main()

{

for(uint16_t x = 0; x <= 255; x++)

{

uint8_t xorkey = x & 0xFF;

for(int i = 0; i < 121; i++)

buf[i] = (data[i] ^ xorkey) + 34;

if(hash() == 0xFB5E)

printf("Valid key: %X\n", xorkey);

}

}

We’re almost done. Put a few breakpoints, debug the program with IDA, netcat the key, decompile the decrypted code and voila’, the flag is in plain sight. It’s quite easy to see that the code puts the flag into the stack before writing out "Congratulations! But wait, where's my flag?":

loc_40107C:

mov bl, 'e'

mov [ebp+var_2B], bl

mov [ebp+var_2A], 't'

mov dl, '_'

mov [ebp+var_29], dl

mov [ebp+var_28], 't'

mov [ebp+var_27], 'u'

mov [ebp+var_26], dl

mov [ebp+var_25], 'b'

mov [ebp+var_24], 'r'

[...]

The flag that got written to the stack was et_tu_brute_force@flare-on.com

Challenge 4: notepad.exe

“You’re using a VM to run these right?”

For the fourth challenge we once again get an executable, this time what seems to be a modified version of Microsoft’s notepad.exe, which reveals a few oddities when opened in PEid or similar tools. The main point here is that the .rsrc section is marked executable and contains the entry point of the file.

Opening the file in IDA shows that it first of all loads some standard library functions, calls sub_1013F30 and then proceeds to jump to the original notepad code. This function iterates over all the PE executable files contained in %USERPROFILE%\flareon2016challenge\ and modifies them. I used the executable from challenge 2 as a test file, and the only section that got changed was .data, going from the original 644 bytes all the way up to 7680. What seems to happen is that the file copies itself into the .data section of all executables it finds in the directory.

The interesting part still has to come though: when modifying an exe, the file tries to open %USERDATA%\flareon2016challenge\key.bin and either writes an 8 byte sequence or reads a 32 byte key. In particular, it reads 8 byte sequences from specific offsets from exe files that have the following compilation timestamps:

2008/11/10 09:40:34 UTC

2016/08/01 00:00:00 UTC

2016/09/08 18:49:06 UTC

2016/09/09 12:54:16 UTC

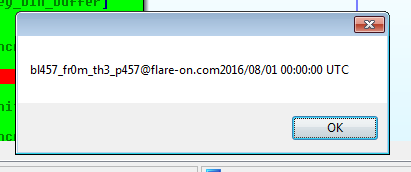

These turned out to be four of the files from last year’s challenge, and I finally managed to get to the flag by jumping around with the debugger, since there were more checks that I didn’t want to reverse. By jumping to the right code section each time one of the four files was being worked on by the application I made it write out the right bytes in key.bin and I was finally greeted with a nice MessageBox:

The flag is bl457_fr0m_th3_p457@flare-on.com

Challenge 5: pewpewboat.exe

“You’re doing great. Let’s take a break from all these hard challenges and play a little game.”

For the fifth challenge we get a game. It’s called pewpewboat.exe, but it turns out it actually is an x64 ELF executable for linux. When we run it, it’s one of the simple “shoot all the boats” games, but we quickly find out that the boats really are uppercase letters.

Between each of the levels there was an annoying “NotMD5Hash” minigame, which asked for the hexadecimal of the bitwise negation of the MD5 hash of some 4 character random string. I just edited it out in IDA (for those interested, it’s function sub_403530 and to edit it out I replaced the call instruction that executed it at address 403BE0 with NOPs). Then it was time to run through the game, keeping track of all the letters encountered in the various levels. At the end of level 10, I was prompted with the following message:

Rank: Congratulation!

Aye!PEWYouPEWfoundPEWsomePEWlettersPEWdidPEWya?PEWToPEWfindPEWwhatPEWyou'rePEWlookingPEWfor,PEWyou'llPEWwantPEWtoPEWre-orderPEWthem:PEW9,PEW1,PEW2,PEW7,PEW3,PEW5,PEW6,PEW5,PEW8,PEW0,PEW2,PEW3,PEW5,PEW6,PEW1,PEW4.PEWNextPEWyouPEWletPEW13PEWROTPEWinPEWthePEWsea!PEWTHEPEWFINALPEWSECRETPEWCANPEWBEPEWFOUNDPEWWITHPEWONLYPEWTHEPEWUPPERPEWCASE.

Thanks for playing!

Which, made more readable, becomes:

You found some letters did ya? To find what you're looking for, you'll want to re-order them: 9, 1, 2, 7, 3, 5, 6, 5, 8, 0, 2, 3, 5, 6, 1, 4. Next you let 13 ROT in the sea! THE FINAL SECRET CAN BE FOUND WITH ONLY THE UPPER CASE.

So that’s what I did. I took the 10 letters ("FHGUZREJVO"), reordered them as instructed and run them through ROT13 to get to "BUTWHEREISTHERUM". I still had to figure out what to do with this new key I obtained, so I went back to IDA and found that the code would happily accept a 16 character string instead of a coordinate.

I put my key in and after a few seconds of delay I got the flag: y0u__sUnK_mY__P3Wp3w_b04t@flare-on.com

Turns out that the delay was caused by the code running MD5 2^24 times on the input string before using it to decrypt the flag, presumably to make sure that nobody would just bruteforce the key.

Challenge 6: payload.dll

“I hope you enjoyed your game. I know I did. We will now return to the topic of cyberspace electronic computer hacking and digital software reverse engineering.”

The sixth challenge revolves aroung a 64 bit library, payload.dll, which seemed to contain only one exported function, EntryPoint. But when I tried to run it with rundll32, I encountered the first problem: EntryPoint didn’t seem to be there anymore when the library was loaded.

After loading the dll up in IDA, I found out that it would rewrite its export table at startup so that the exported function was another one, basophileslapsscrapping. The weirdness of the name will become clear soon. So I wrote a small program that would call the function by ordinal, in order not to have any problems with the name:

#include <cstdio>

#include <windows.h>

typedef void (*func_t)(long long, long long, long long, long long);

int main()

{

HINSTANCE dll = LoadLibrary("payload.dll");

if(!dll) printf("No library?\n");

else

{

func_t fn = (func_t) GetProcAddress(dll, MAKEINTRESOURCE(1));

if(!fn) printf("NOFUNC???\n");

else

{

fn(0, 0, 0, 0);

}

}

}

When I run it all I got was an error message in a MessageBox, so I started going deeper with the disassembler and debugger. What I found was that the new entry point, which I’ll call basophiles from now on, would only do its business if the third parameter actually pointed to its name. And so I did, giving it the address of the string in the new export table:

fn(0, 0, (long long) fn - 0x5A50 + 0x403D, 0);

Frankly, I didn’t expect much to happen when I run it, so imagine my surprise when this popped up:

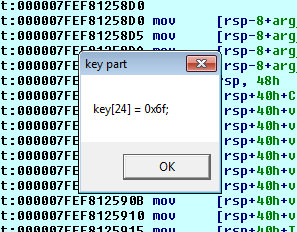

I finally had a byte of the flag. Granted, it was probably just one of the ‘o’s in @flare-on.com, but it was something. All I had to do now was finding out the other bytes. I noticed a big chunk of random looking data at the start of the .text section, from which some bytes had become the new export table when I got that first byte, so I started to think that there could be other export tables encrypted in that data. I finally realized that the library was actually choosing which offset to decrypt based on the current timestamp. In particular, it would divide the sum of the current month and year by 26 and take the remainder, which would then be used as the index of the export table to decrypt.

Travelling in time is kind of hard at the moment, so I changed the index in the debugger to decrypt the various pieces, and each time there would be only a single exported function with some random looking name. The curious fact was that the function was always basophiles. the only thing to change was its exported name. What basophiles would do is read the last byte of the export table timestamp and use it to choose a function to decrypt and execute. I was almost there. All I had to do to obtain the remaining bytes of the flag was to run the binary in the debugger, each time putting a different index in the decryption routine and skipping the function name check in basophiles.

In the end, I got my flag: wuuut-exp0rts@flare-on.com

But I couldn’t just stop there. I had to know what all those weird function names were. Turns out, they were just random words:

fillingmeteorsgeminately

leggykickedflutters

incalculabilitycombustionsolvency

crappingrewardsanctity

evolvablepollutantgavial

ammoniatesignifiesshampoo

majesticallyunmarredcoagulate

roommatedecapitateavoider

fiendishlylicentiouslycolouristic

sororityfoxyboatbill

dissimilitudeaggregativewracks

allophoneobservesbashfullness

incuriousfatherlinessmisanthropically

screensassonantprofessionalisms

religionistmightplaythings

airglowexactlyviscount

thonggeotropicermines

gladdingcocottekilotons

diagrammaticallyhotfootsid

corkelettermenheraldically

ulnacontemptuouscaps

impureinternationalisedlaureates

anarchisticbuttonedexhibitionistic

tantalitemimicryslatted

basophileslapsscrapping

orphanedirreproducibleconfidences

Conclusions

Yes, I’m already drawing my conclusions here. After I finished challenge six school started and, while spending a lot of time on challenge seven, I just couldn’t finish it in the time I had. I’m hoping to do better next year, yet I’m satisfied enough for the results I got, this being the first time I participated in the Flare-On competition.

Out of the six challenges I solved, some of the nicest were the last two, with the sixth being slightly evil in its management of export tables. The fourth challenge took a bit more guessing than I was expecting to find the right files, but in the end I enjoyed all of them.